Finding the Five Unity Principles in Buddhism

By Rev. Paul John Roach

Unity teachings are based on five universal spiritual principles drawn from the world’s major faiths. In his book, Unity and World Religions, Paul John Roach tells how those five principles show up in Buddhist teachings and practices. The Unity principles have been added to this excerpt for clarity.

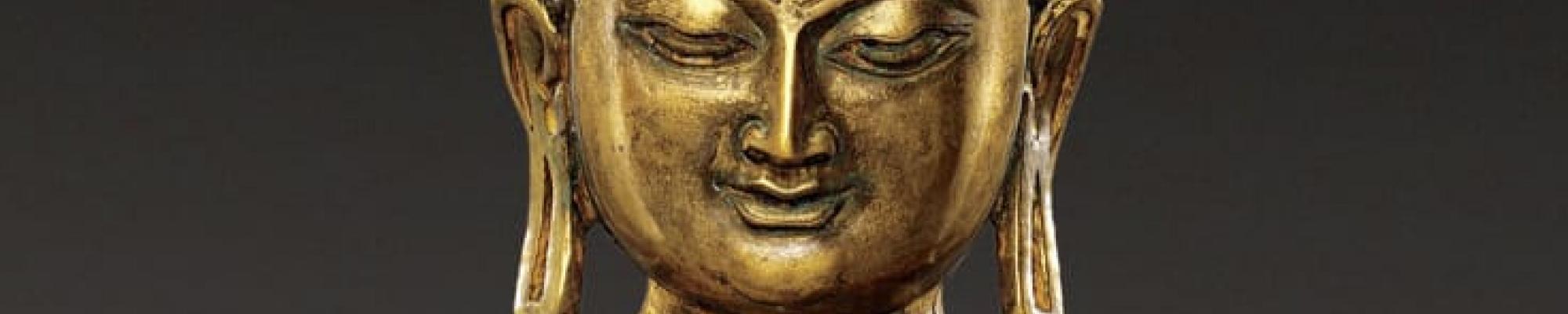

Buddhism has been referred to as the light of Asia and provides the most systematic and insightful spiritual psychology known to humankind. The founder, Gautama Siddhartha the Buddha, was not concerned with speculative theology but rather with philosophically precise yet practical ways to find freedom from suffering and the inherent dissatisfaction of the human condition …

Like Jesus, the Buddha was in rebellion from the orthodoxies of his time. Where Jesus was critical of the scribes and Pharisees for following the outer observance of the law while neglecting the inner Truth, so Buddha was critical of the dogmatic and heavily ritualized teachings of the Brahmin priests of his day.

The Buddha avoided becoming involved in theological and doctrinal arguments and spoke very little about God. His primary concern was to relieve suffering and provide an effective template for self-transformation. He counseled against a reliance on authority and taught that doubt was healthy. His emphasis was always on seeing for oneself …

Unity Principle One: God is everywhere and always present in every circumstance. This divine energy underlies and animates all of existence.

In terms of the first Unity principle, then, we can say that, although Buddhism doesn’t speak of God as an entity, it certainly does approach the idea of wisdom consciousness or presence using the term Buddhi or Bodhi. Later Buddhist systems like the Mahayana speak of sunyata or emptiness as the essence of being, which has similarities with the apophatic tradition of Christianity and Hinduism, the way of apparent negation.

Personally, I find the lack of fine philosophical niceties in Buddhism refreshing. The clarity of focus is attractive. This is illustrated in the famous parable of the arrow, where the Buddha tells about a man who has been wounded by a poisonous arrow. The man and his physician discuss a number of matters concerning this arrow before they are willing to remove it. For example, which caste did the assailant belong to? What was his name? What was his height and shape? Was he black or white? What village was he from? Before they could answer any of these questions, the man died.

In this parable Buddha alludes to the ineffective nature of useless speculation about Truth, especially when it does not help with the matter at hand. Again, the Buddha’s main focus was to share ways to cure the problem …

Unity Principle Two: Human beings are innately good because they are connected to and an expression of Spirit.

The Unity second principle of the inherent spark of divinity within all beings appears to be refuted by the Buddha’s concept of no self, but this is not exactly true. The Buddha’s intent was to help humanity move beyond the trance of conditionality that leads to suffering. He is not interested in ideas about something, however exalted, but rather in direct experience through awakening.

Holding ideas about the nature of God or Spirit is no substitute to experiencing the freedom of Nirvana. The fact that the Buddha affirmed this awakening is possible is proof of his high regard for the nobility of humanity …

Unity Principle Three: Our thoughts have creative power to influence events and determine our experiences.

As we can imagine, Buddhism provides an endless variety of approaches and insights into the third Unity principle of creative mind action. Indeed, I could say that Buddhism provides a systematic investigation of the “problem” of the human condition as well as a profound examination of the solution.

Later Buddhist texts offer metaphysical and philosophical investigations that approach depths of mystical insight that are similar to the teachings of such great mystics as Meister Eckhart and Islamic masters …

Just as the law of mind action allows for choice—we reap what we sow—in the same way the Buddha taught that our mind both traps us in endless cycles of karma and rebirth or frees us to experience the unconditional.

Grasping for enlightenment, in the Buddha’s view, would be counterproductive. There is a higher or third way … the way of creative letting be. Dogen, the great Zen master of 12th-century Japan, wrote, “The Buddha way is, basically, leaping clear of the many and the one.” Another teacher, Huang Po, said of the enlightened awareness:

It is void, omnipresent, silent, pure;

it is glorious and mysterious peaceful joy

—and that is all.

How do we obtain it? By direct experience. Laws, doctrines, techniques are important, but they can only get us so far.

Unity is attained when we cease to make comparisons between them and us, right and wrong, liked and disliked.

The lines between the core teachings, meditation practices, and enlightened activity are fluid within Buddhism. This is one of its strengths and appeals. It is a truly integrated spiritual approach.

Unity Principle Four: Prayer and meditation connect and align us to our own spiritual nature and to God.

Buddhism offers an array of meditative practices. Theravada Buddhism elucidates the twin practices of samatha or calm abiding, and vipassana, clear seeing or mindfulness.

Watching one’s breath, body, thoughts, and mental processes can lead to deeper and deeper levels of awareness and insight … In recent years, mindfulness meditation has become quite popular in the West, providing, as it does, a pragmatic way to calm the monkey mind. It appeals to the overactive Western mind by allowing the mind to watch itself.

The Theravada school also places a strong emphasis on Metta or loving-kindness practice that extends benevolence to all beings.

In the Mahayana tradition there is great meditative focus on the concept of Sunyata or emptiness. This emptiness is not nothingness in the nihilistic sense, but rather an understanding of spaciousness and unconditionality, a void full of all possibility, which some Christian mystics have referred to as a plenum void. This emptiness interpenetrates form.

The Heart Sutra, an essential text for Zen Buddhists, states that, “Form is emptiness and emptiness is form.” It requires intuitive or unitive awareness to fully understand this apparent contradiction …

Principle Five: It is not enough to understand spiritual teachings. We must apply our learning in all areas of life, incorporating them into our thoughts, words, and actions.

The lines between the core teachings, meditation practices, and enlightened activity are fluid within Buddhism. This is one of its strengths and appeals. It is a truly integrated spiritual approach.

The seamless nature of Buddhism is encapsulated in what is referred to as the Three Jewels, which are the Buddha (the teacher), the dharma (the teaching), and the sangha (the community) …

This trinity is the stable three-legged stool that provides Buddhism with a firm foundation. Looked at metaphysically it could be defined as the spirit, mind, and body of the tradition. We could liken it to Jesus’ declaration, “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” The Christ-centered way elucidates Truth so that we are empowered to live the Christ-filled life.

Like jewels, each of the three aspects illumine, refract, and inform the others. In the same way the Three Jewels reinforce the power and effectiveness of the Buddha’s teaching …

I have always felt that Jesus Christ was a bodhisattva whether he knew Buddhist teaching or not. It is not inconceivable that he might have heard the dharma because in the centuries prior to his birth, Buddhism had established a presence in Afghanistan and Persia and other parts of the Middle East.

Jesus’ final words in the Gospel of Matthew, “And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age,” is an altruistic dedication to help and serve others. Charles Fillmore said that because of Jesus’ resurrection, the electrons of his life blood were now available throughout the cosmos, which speaks to the intimate connection of the regenerated body and Spirit …

As a Unity minister I have found the teachings of Buddhism to be a great companion on the spiritual path. Their depth, psychologically rich insight, humor, sheer variety, and honest humanity are endlessly useful.

Adapted from Unity and World Religions by Paul John Roach.

About the Author

Rev. Paul John Roach is a writer and world traveler who served as a minister based in Fort Worth, Texas; as a board member for Unity World Headquarters; and hosted World Spirituality on Unity Online Radio. Visit pauljohnroach.com.